the view from lake county

|

|

When an undiversified economy experiences stress, the larger social, cultural, and ecological systems in which that economy is embedded inevitably suffer collateral damage. When Lake County experienced back-to-back freezes in the mid-1980s, decimating its citrus industry, the broader social, cultural, and ecological landscapes absorbed the shocks in ways that continue to reverberate today.

Citrus was once King in Lake County, Florida. But back-to-back freezes in ‘83 to ’85 changed all that. In 1983, before the first freeze, Lake County was cultivating 117,000 acres of citrus; by the end of 1985 that was down 90 percent to a mere 13,000. In 1989 an Orlando Sentinel reporter quoted a citrus specialist for the Lake County Agricultural Extension Service as saying, "Lake County will never be the citrus producer it once was because of the freezes and urbanization pressure. I classify the county now as a transition county." That transition has not always been a smooth one. Following the freezes, citrus farmers and their families had to decide whether to hang on or whether it was time to get out of the agriculture business altogether. With the tourism and real estate market booming in Orlando and Disneyland to the east and south, many farm families seized the opportunity to cash out. “A lot did that and when they did Lake County was prime for development,” says Cadwell. “You had all this agricultural acreage that was already open area. From that day forward our economy was built on growth in real estate and the jobs all went into home building.” |

|

Initially that development created a nice spike in the local economy. The early construction of self-contained retirement communities didn’t draw heavily on municipal services. But over time as the population mushroomed— from 126,325 in 1985 to 307,964 in 2008—and single-family, cookie-cutter subdivisions multiplied, not only did it impact the county’s rural character, but also school systems, parks, and infrastructure were increasingly taxed.

The lack of a significant diversified commercial tax base to support the growing population impacted the health of social networks as well as the fiscal budget. Job opportunities in the county, outside the low-wage service sector, were scarce. Although Lake County’s raw employment numbers were good pre-recession they masked a higher “underemployment” rate. Says Cadwell: “We didn’t have the type of jobs to best utilize skills and help make a good living. If you didn’t work for government, the school board or a hospital you didn't get paid much. You could get a job but a lifestyle-changing job, no.” Consequently, most of the breadwinners who populated those new subdivisions were seeking employment outside of Lake County. “They were not part of the local Lions Club or Kiwanis club,” Cadwell reports, “they were not involved in the schools with their kids, their jobs were 45 min to an hour away. So our daytime community lacked vitality.” |

The recession years gave Lake County leaders an opportunity to pause, reflect on past mistakes, and to make concerted efforts to diversify the local economy in ways that would enhance the natural and human capital upon which that economy’s health and sustainability depended.

|

It is fair to say that Lake County civic, government, and business leaders failed to anticipate the residual effects of the unchecked growth they unleashed during the first wave of the residential housing boom. “I was part of it too,” Cadwell candidly admits. “We were doing what we thought was right at the time.” Today, as Lake County emerges from the recession, Cadwell believes growth advocates have grown wiser and their perspectives have been tempered by both experience and necessity.

The recession years gave Lake County leaders an opportunity to pause, reflect on past mistakes, and to make concerted efforts to diversify the local economy in ways that would enhance the natural and human capital upon which that economy’s health and sustainability depended. Some of the diversification came about naturally, for example, through the growing demand for retirement community health services businesses, which offered better paying jobs than typical of the service industry. Lake-Sumter State College and University of Central Florida, both in expansion mode, created satellite campus in the county that also added a welcome cultural texture to the community fabric. The added benefit, says Cadwell, was that “people could get degrees without leaving the county so they would be more a part of the community as they got their education.” In manufacturing the county began partnering with Lake Technical College in 2012 on an educational center where locals could train for jobs in the high-wage technology sector. “We have also always said we are flexible to businesses that want to create good paying jobs,” says Cadwell. Lake County built the Christopher C. Ford Park in Groveland to create a home for higher wage manufacturing and distribution jobs. “Additionally, we created the Lake County Economic Action Plan, which gave us a pathway to help our existing businesses grow and to give us the potential to attract new businesses to Lake County,” adds Cadwell. |

“Because it is a protected area the northern part will always have a different look and feel from the rest of Central Florida,” says Cadwell.

|

Even now as the local real estate economy begins to revive, new residential housing growth will be restrained thanks to the creation of the Wekiva River Mitigation Bank that protects from development over 1600 acres of significant wildlife habitat, including the dwindling population of Florida Black bear, and one of the few near-pristine river systems in Central Florida. The mitigation bank has been a mixed, but overall positive, blessing for the local economy, says Cadwell. “When you take hundreds of acres out of development it affects how you can develop goods and services and it affects growth overall,” he reports.

But, he notes, it has also attracted sports and eco-tourist dollars to north Lake County. “Because it is a protected area the northern part will always have a different look and feel from the rest of Central Florida,” says Cadwell. “We call it ‘Real Florida, Real Close.’ So that is another niche we have realized as daytime visitors patronize local businesses and contribute their sales tax and room tax dollars. That has been a big plus.”

|

It is not as simple as build downtown housing and they will come. You need to ensure the amenities are in place to create a sense of place that will attract downtown residents.”

|

The more foresighted among county leaders have also made concerted efforts to take the pressure off growth in rural Lake County by encouraging residential development in the downtowns of Lake County’s 14 small cities. “Very slowly it is happening,” says Cadwell. “They are starting to do infill and trying to build rewalkable communities. I call them rewalkable because they once were. It is about understanding the only way these downtowns can survive is pedestrian traffic. To have a sustainable downtown you need housing close by. We have worked with several of our municipalities to try to focus on what makes them unique and try to figure how they can facilitate downtown realization projects.

It is not as simple as build downtown housing and they will come. You need to ensure the amenities are in place to create a sense of place that will attract downtown residents.” A new type of development called a “sector plan,” which ties housing creation directly to job creation, is now being contemplated in southernmost part of the county, where development pressures are greatest. The Lake County government websites states: “A successful sector planning effort will enable Lake County to diversify its economy, protect natural resources and strengthen its connectivity with other economic hubs in the region.” The plan, called Wellness Way, which could potentially cover over 16,000 acres with new residential development, is working its way through the planning process, but it is not without its critics. Luring residents out of their cars and onto public transportation is a challenge for Lake County. But early efforts have achieved some limited success. Cadwell, who also serves as chair of the Central Florida Expressway Authority, is also a public transportation advocate. He reports that the LakeXpress, a traditional bus service, was the county’s first venture into public transport in 2007, and has enjoyed better ridership than anticipated, and plans are to extend the system. “We are looking at new legislation that created the Central Florida Expressway,” says Cadwell. “As part of that one of our tasks is to look at multi-modal transportation. I hope we will be able to grow public transport. None of it makes money or breaks even, but is it worth it to the community? Slowly people are deciding. You can’t keep building bigger roads at some point you will be go too wide and too high, not to mention the downside of the carbon footprint. However, carbon footprints are not much talked about in Lake County, nor are the larger question of climate change. Lake County is fortunate to sit on one of the biggest underground aquifers and is so far inland that sea level rise has not impacted it as it has coastal regions of Florida. Lake County has also been spared severe hurricane weather in recent years. “I am not saying we are ignoring climate change but we have not had scientific discussion about it and if we did it would be a divided conversation,” Cadwell reports. |

|

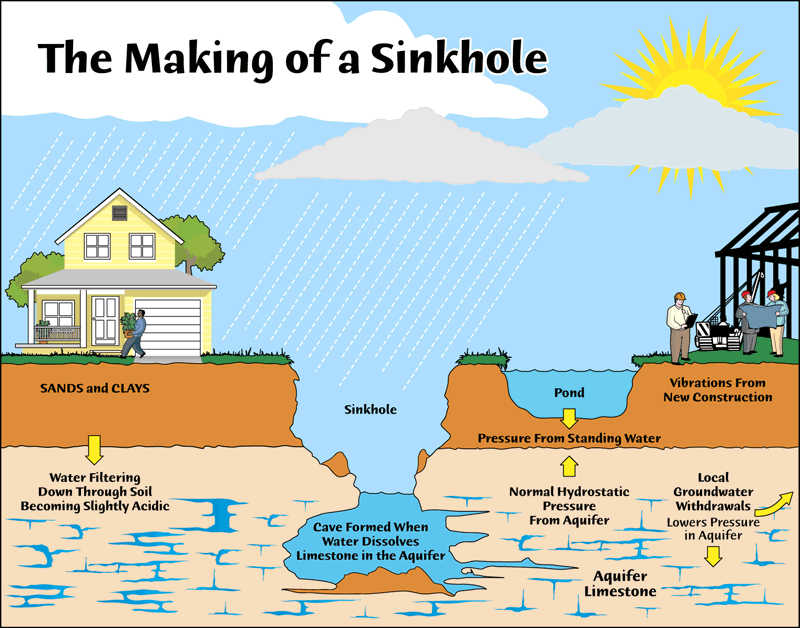

Nonetheless, as development picks up, concerns are rising about access to water. The increased tapping of the St. John’s River for drinking water troubles many local residents. And when water levels of the county’s 1000 lakes decline during drought seasons, creating dangerous sinkholes over the collapsing limestone that caps the aquifer, it is a reminder to all in Lake County that growth imperatives must be balanced with those holistic values that ensure the quality of all life in Lake County.

|

more on the view from lake county

An Organic Farmer Tells His Cautionary Tale

Hugh Kent, owner of King Grove Organic Farm, says that he is deeply troubled by changes in the political and economic landscape in Lake County and Central Florida that are reversing the innovative land-use codes that so many local advocates worked so hard to put in place. “We were able to do some really good things with zoning before the recession,” he reports. “But at the beginning of the economic downturn, when people stopped hearing backup signals on earth moving equipment, they just forgot about what the rampant development was doing to the land around here."

|

US Green Chamber CEO Michelle Thatcher Crafts a Careful Outreach Strategy

Michelle Thatcher, CE0 and co-founder of the over 1000 member U.S. Green Chamber of Commerce grew up in one of the “greenest” communities in Washington State. Now based in the very different social and political climate of Central Florida, she has crafted an outreach program for the Green Chamber that is carefully tailored to a business community that may not always be initially receptive to its message.

READ MORE |

Economic Growth Director Robert Chandler’s Diversification StrategyRobert Chandler was the person who was going to leave Lake County where he grew up and never come back. But after a sojourn to North Carolina where he attended Davidson College, he married a Lake County native. Although they initially settled in Orlando, they returned to Lake four years ago when Robert accepted a job as Lake County’s coordinator of economic development and tourism and in March 2015 was named the county’s first ever Director of Economic Growth. Robert has never regretted the decision.

READ MORE |